For the last twelve years, our family has had a Christmas tradition that doesn’t involve matching pajamas, elaborate travel plans, or sleeping in on Christmas morning.

When Lincoln was two, Amy and I decided we wanted to create a family tradition—something that would matter, something Lincoln (and any future kids we might have) would grow up doing together. We landed on the idea of a community Christmas dinner.

The first year was… ambitious.

I wildly overestimated how many people would show up. We had an unbelievable amount of food left over. Tons. Enough that we started flipping through the phone book—yes, an actual phone book—and calling people to ask if they wanted meals.

One of those calls led us to a family that had moved to town just two days earlier. I don’t remember all the details, but I do remember this: they didn’t have food, and the grocery store was closed. Because we had cooked too much, we were able to give them enough food to last a week.

That alone would have made the whole thing worth it.

A year or so later, the crowd grew. The fellowship was great. One of the reasons we started the dinner was to provide a Christmas meal for people who might not have the resources to do it themselves—and while there were certainly a few situations like that, I quickly learned something unexpected.

Most of the crowd was made up of empty nesters.

And honestly? The empty nester crowd is awesome.

For many of them, this dinner wasn’t really about the food. It was about sitting across the table from people they hadn’t seen in a long time. People they usually only ran into at the grocery store or passed in the hallway at church. One couple showed up every year about fifteen minutes before the meal started and left about fifteen minutes after it ended—just long enough to visit, laugh, and catch up.

That was the whole point for them.

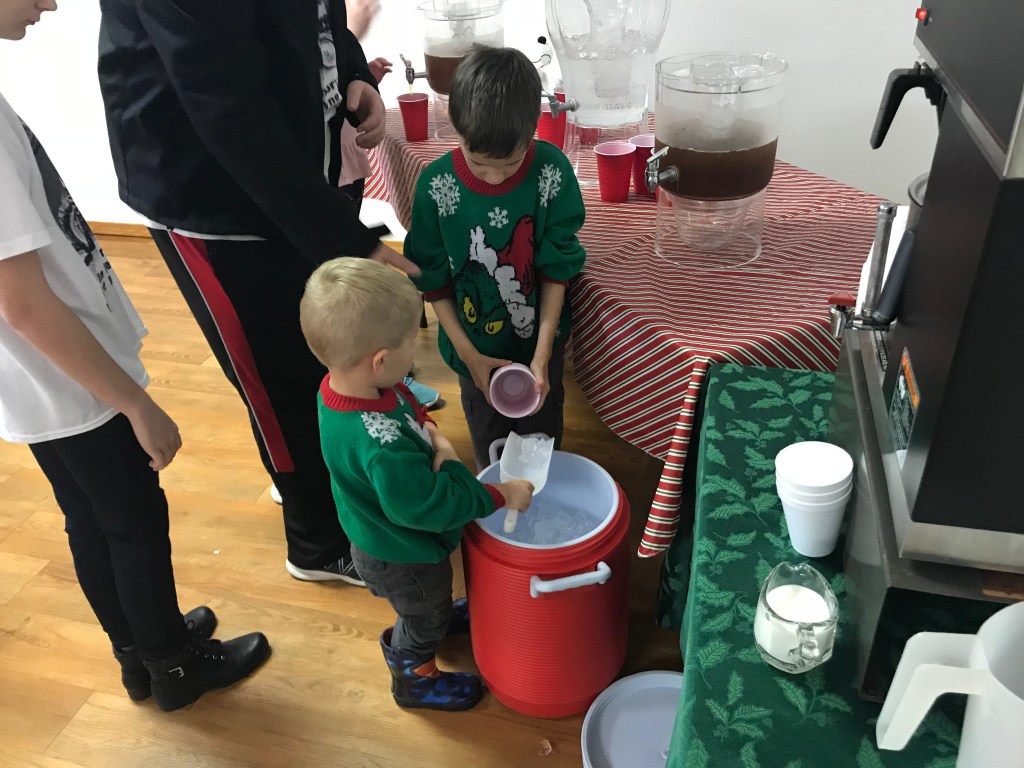

It’s been fun watching the boys grow up with this, too.

I think the dinner has given Andrew a genuine heart for senior adults. This year, he made sure every person had a clean place to sit and a drink ready. He quietly bussed tables the entire time so no one would have to deal with trash. No one told him to do that. He just noticed and acted.

Lincoln loves the deliveries. He can’t drive yet, obviously, but he enjoys riding along and taking meals to people’s homes. It pushes him slightly out of his comfort zone. It requires conversation—though thankfully for him, the conversations are usually short because there are more deliveries to make. Not everyone is wired like Andrew and me, and that’s okay.

Over the years, there have been other good options for how we could spend Christmas Day. And I’m grateful for that. Family matters. Time together matters. Those are gifts.

But what has surprised me is that this dinner has never felt like something we have to do. It’s something the boys want to do.

When I’ve asked if they’d rather skip it or do something else, the answer has always been the same. They look forward to it. They plan around it. For them, Christmas Day isn’t complete until the tables are set, the food is served, and the deliveries are made.

Another thing I didn’t anticipate when we started this twelve years ago is how much memory this meal would carry.

Those of us who have been around since the beginning find ourselves reminiscing—not just about past dinners, but about people. Families. Widows and widowers. Volunteers and regulars who showed up year after year. Some of them are no longer with us now. They’ve gone on to be with the Lord, and I miss them terribly.

There’s something sacred about remembering them together. About telling stories. About laughing at old moments and quietly acknowledging the empty chairs. Christmas has a way of doing that—it holds joy and loss at the same table.

This dinner has become a time of reflection and remembrance as much as service. A reminder that life is brief, relationships matter, and showing up counts more than we realize in the moment.

I do wonder what this will look like someday. Will the boys still live in Okeene? Will they want to help when they’re grown, or will this take a different shape entirely? Maybe they’ll start something like this in their own communities. That would be pretty incredible.

I wonder how their future families will feel about it. Will their spouses love it, tolerate it, or roll their eyes a little? Will this tradition carry into the next generation, or will it simply become a good memory—something that quietly helped shape who they became?

I don’t know the answers to any of that.

But I do know this: for twelve Christmases, they have chosen to show up. They’ve learned to serve. They’ve learned to notice people. And they’ve learned that some things are worth building your day—and maybe your life—around.

And maybe that’s how traditions last — not by being preserved, but by shaping the people who carry them.